Your cart is currently empty!

Memorial Day

Today is (hypothetically) a “holiday”, and is practically viewed as the ‘official’ start of summer, but it’s a holiday with a bit of a more somber purpose- it is supposed to be be about enjoying what’s good about our society and culture while remembering the sacrifices that made this society possible. At least, that’s the big picture presentation. The shorthand version is that it’s also about honoring and remembering those who have died in the service of the nation- veterans, primarily.

America has a checkered history with military service. Conscription has been a facet of American life for the past 150 years; most practically for us today, our grandfathers were drafted for service in Vietnam, and although the practice was suspended after our defeat in that war, the mechanism still exists. More recently, we’ve fought three wars and a host of “peacekeeping” actions across three continents and untold other actions across the globe for the past forty years with a volunteer force. Some of those were completely necessary, valid, prudent and constructive missions. Some were well-intentioned campaigns that turned out to be failures. And some were cynical exercises of power that hastened our defeats, degraded our forces and reputation, and actively corroded our national interests in the name of vague political promises. Some were all three at once, and some were none of the above- just normal actions. There have been high highs (victory over fascism, the preservation of a free and secure and prosperous South Korea, victory in the Cold War, the end of the Bosnian Civil War), some meh mids (preserving oil profits in Desert Storm, “liberating” the Iraqis from Saddam), and some very disappointing failures (Cambodia, Vietnam, Afghanistan).

When I was twelve years old, my grandfather took me to a movie…”We Were Soldiers”, a film adaptation of the experiences of the legendary Air Cav’s 1965 Ia Drang campaign. Mel Gibson portrays the stoic, tough and determined Hal Moore, a real-life legend in the Army’s storied history, who led his men to a hard-fought victory. Grandpa made it about 45 minutes into the movie, but when the shooting started, he left the theater. I found him outside, leaning on a wall, anxious. At the time, I had no idea that a grown man would cry- it was a bit embarrassing to a kid. I’d known he was a Vietnam veteran, but I had no idea what that meant. I found out that he grew up around the Air Force, moved around by his father’s assignments (NCO with the 8th Air Force, then Strategic Air Command), and that his uncle had died in 1944 somewhere over Western Europe when his bomber exploded. His paternal grandfather had been a Texas Ranger, another grandfather had served in the AEF of World War 1. Art moved to California in his sophomore year of high school, missing the critical California state geography class normally taken freshman year. He’d gone to school, played sports, and grown up in the mid-60s. But when it came time for graduation and college, that one hanging class held him up…an incomplete high-school diploma would take six weeks to fulfill, but that also derailed college plans and the all-important deferment that would have protected him from the draft.

Back in the mid-Sixties, the draft was hyper-local…county draft boards composed of selectmen assembled rosters of all eligible persons, which functionally meant that they were able to protect their favorites (employees, friends, family, functionaries, etc) from the draft while offering the marginalized members of the community the exciting opportunity for service in Vietnam. (Of course, volunteers were always welcome). Art was a relative newcomer to the community, didn’t have local money or family name or political power, and didn’t have the eye of a patron. He was dating a girl who worked for the draft board as a clerk, so when they met for lunch, she helpfully slipped him a notice that he was being drafted for service in the Marine Corps. Art told me that he walked away from that, straight into the loving arms of the United States Army. As he put it, “I was going to go. The only question was how, and I thought I’d be able to chart my own course a bit better as a volunteer.”

Art trained for nearly a year- basic training, typing school, armorer’s school, Ranger school. He was under the impression that more training would burnish his wings, earn him time credit and a specialization, and keep him out of the jungle. Maybe even out of Vietnam entirely. He was half-right- when he arrived in Vietnam, he was assigned to the 71st Helicopter Attack Company, serving as a door gunner and flight crewman overhead. They flew dozens of missions a day, everything from routine air-mail and R&R flights to medevacs and troop insertions and field resupply missions, without plans or backup. Just a call and rotor blades and an M-60 spewing 7.62 NATO into the jungle. Art was 19 years old when he arrived in Vietnam. He told me about his first day in-country being handed a helmet, a flak jacket and a joint and told he’d either live or die based on how that day went. He watched men die up-close and other men disappear into the jungle. He served out his first tour, and then got orders back to Vietnam, so he declined those orders and ended up staying with the 71st. At some point, he went AWOL and spent six weeks back in Petaluma, CA before he was arrested for public intoxication, handcuffed, and flown back to South Vietnam by an Air Force MP he described as “the biggest, cleanest gorilla I’d ever seen.” His first sergeant picked him up, handed him a duffel bag, and huge went back to work. A few months later, he was flying into a hot LZ when a 7.62 x 39 rifle bullet shattered his left femur. Art didn’t die that day, but he spent eight months in hospitals and rehabilitation, then discharge to the civilian world with a Purple Heart, the appreciation of Richard Nixon and a world that viewed him as inconvenient at best. There was little support for them- PTSD was known but not acknowledged, and the monthly pension for lifelong pain and the complications that we now know bare-handing Agent Orange bricks was a salve, not a fix. He tried alcohol, and marijuana, and some harder drugs too. He ended relationships, drifted through jobs and places, and tried to find peace. Eventually, he did, for a time…and then that faded and he declined and died. Vietnam didn’t kill him in 1969, but it defined a lot of his life.

Art Hathaway was ripped away from his home, tossed into a fight for survival disguised as a mission to export American values and our way of life to an unwilling population, and nearly died doing it. 58,220 Americans did die in those jungles, for a net defeat. Forty years later, I swore that same oath, and deployed to “Operation Iraqi Freedom”, where we were trying to do essentially the same thing for another semi-accepting group of third-world tribesmen who didn’t share our fundamental values, didn’t actually want any of the promise we’d offered them, and didn’t hold up their end of the bargains we’d made with them. It was nowhere near as violent or traumatic as Art’s experience, and it left far less of a corrosive affect on me. But that’s not the point. 4,419 Americans died in the course of OIF, 31,993 were “officially” wounded in action. Simultaneously, and with many of the same people, 2,350 Americans died in Afghanistan and more than 20,000 were wounded.

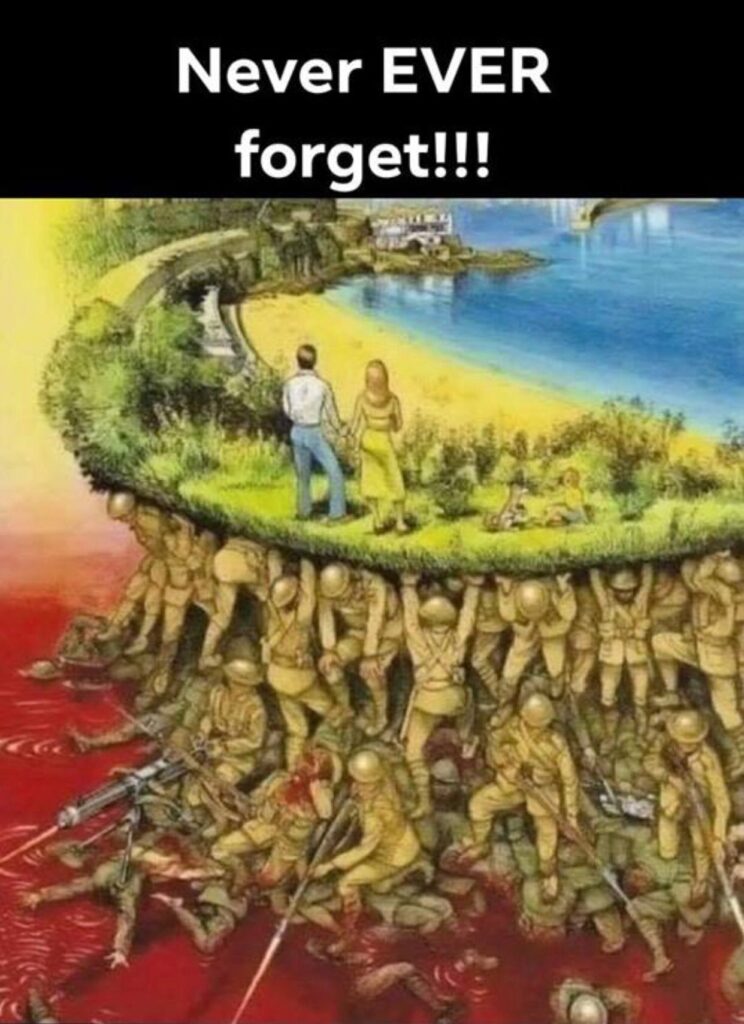

Maybe those sacrifices will be worth it. It’s impossible to see the future, after all, and Iraq has somewhat stabilized from the horrific sectarian violence that devoured it during our active occupation. Vietnam today is a thriving capitalist society that is a significant US trading partner. Germany is one of our closest allies. South Korea is a thriving capitalist society thanks to the sacrifices of 54,246 American lives and 103,284 wounds. Japan’s fervent, barbaric Imperial era was ended by tens of thousands of American lives more. Our nation itself was stitched back together by the approximately 600,000 lives of Union and Confederate soldiers lost in the course of our Civil War. And all those numbers take us to the conclusion of this essay- that Memorial Day isn’t just a four-day weekend and a barbecue or a wreath-laying ceremony for venal politicians to showcase how much they “care”.

Remember how I mentioned that Art was “inconvenient” when he got home? Well, fellow Americans, here’s a hard truth…in our society, anything that detracts from the image of America is inconvenient for us. Inconvenient for our leaders, inconvenient for our politicians and our media and our money and our reputation. Victory and success are celebrated, but victory doesn’t need a memorial. Success is its own memory, one we all want to live in. But real life isn’t just success and victory. Real life is death and wounds and trauma and consequences thereof. Real life is putting a Vietnam veteran into LA County jail for six months because he was caught with marijuana. Real life is losing good friends in a 2013 IED strike that I should have been at, more friends losing legs, and America losing good people. Real life is the demoralizing realization that it was hard to immediately find the article memorializing Coty because of another mass-casualty IED strike that blends together 12 years later.

And that’s the actual, core, real purpose of Memorial Day. The dead are remembered, as best as possible, by those who knew them in life, but humans and life move on. We remember who they were, but every day, their memories get a little fainter and we adapt. Death is inevitable, after all, and we find new meanings and joys in our lives. The dead need nothing- no funding, no food, no shelter or clothes or even recognition. The real purpose of remembering the dead is for us to remember the circumstances that led to their deaths. It’s for us to remember what we did to get them in that circumstance, and for us to use that deliberation to figure out how to keep it from happening again. Remember that when someone is banging the war drums, we need to remember what’s at stake, consider what and how action is proposed, and we need to act decisively and powerfully so as to succeed and minimize the sacrifices that will be made implementing that agenda. Memorial Day is a somber, stark reminder that we as citizens need to think about our collective actions, lest it be our loved one with a name carved in marble.

by

Tags:

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.